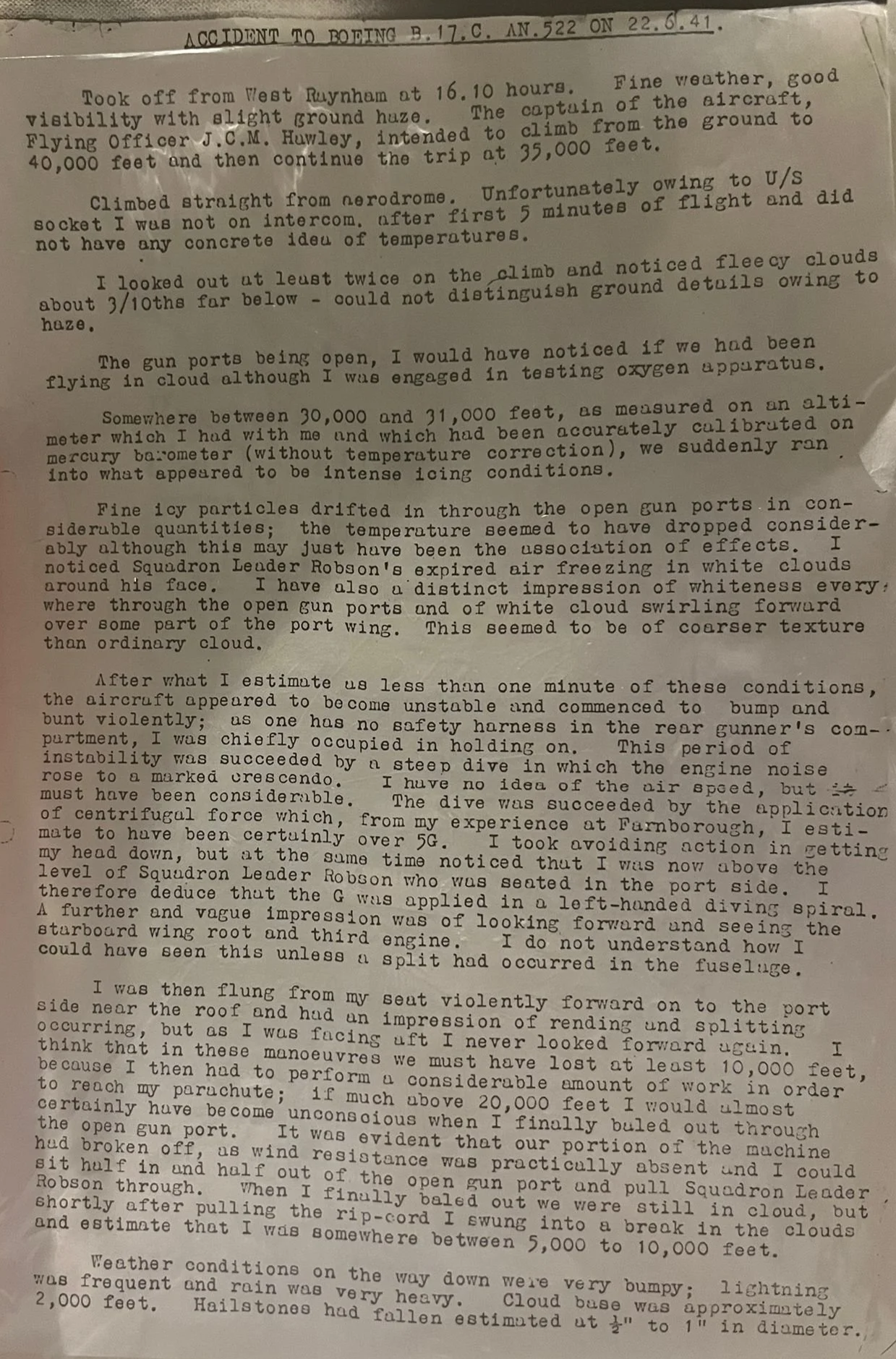

High-Altitude Accident Report,

22 June 1941

Account by Air Vice-Marshal William Kilpatrick Stewart CB, CBE, AFC

This document is a first-person account written by William Kilpatrick Stewart following a high-altitude test flight accident involving a Boeing B-17C (AN.522) on 22 June 1941.

The aircraft departed RAF West Raynham at 16:10 hours in fine weather, with good visibility and slight ground haze. The planned flight profile involved a direct climb from the aerodrome to 40,000 feet, followed by cruise at 35,000 feet. The aircraft was captained by Flying Officer J. C. M. Hawley.

During the initial stages of the climb, Stewart was engaged in testing oxygen equipment. For the first five minutes of flight, the temperature measuring socket was not connected, resulting in a lack of reliable temperature readings. Although thin cloud was observed below the aircraft, the crew did not initially believe they were flying in cloud conditions.

At approximately 30,000 to 31,000 feet, the aircraft suddenly encountered severe icing. Fine ice particles entered through the open gun ports, accompanied by a rapid drop in temperature. Dense white cloud and swirling icy matter were observed within the aircraft and around the port wing, appearing coarser and more severe than ordinary cloud formations.

Within less than a minute, the aircraft became violently unstable. It began to buffet heavily and entered a steep, uncontrolled dive, accompanied by a marked increase in engine noise. Stewart estimated that centrifugal forces exceeded 5G, based on his prior experience with acceleration testing at Farnborough. The aircraft entered a left-hand diving spiral, during which Stewart noted significant displacement of his own body position relative to other crew members, confirming the severity of the forces involved.

Structural failure followed. A split developed in the fuselage, and Stewart was thrown violently forward, with the clear impression that the aircraft was breaking apart. He estimated that the aircraft lost at least 10,000 feet during the descent and noted that loss of consciousness would likely have occurred had the breakup taken place at greater altitude.

Stewart was ultimately forced out through an open gun port after part of the aircraft structure detached, reducing wind resistance. He observed Squadron Leader Robson exit the aircraft and deployed his parachute, which opened between approximately 5,000 and 10,000 feet.

The descent took place in highly adverse weather conditions, including severe turbulence, heavy rain, frequent lightning, and hailstones estimated between 12 and 25 millimetres in diameter. The cloud base was assessed at approximately 2,000 feet.

This report provides a rare and detailed contemporary account of the environmental hazards, physiological stresses, and structural risks associated with early high-altitude flight. It illustrates the conditions under which Stewart and his colleagues gathered critical data that would later contribute directly to advances in aviation medicine, aircrew safety, and aircraft design.